Soo Locks, Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan/Ontario, USA/Canada

|

Read more about How the Soo Locks Were Made at Lake Superior Magazine. The Paul R. Tregurtha--the largest ship on the Great Lakes--was the first to navigate the Soo Locks and into ice-covered Lake Superior in this time-lapse video:

Travel a bit further back in time and watch the first historical passage through the Great Lakes winter season, circa 1949, in this silent movie from the US Archives.

|

<

>

Lake Superior is the largest of the Great Lakes, and the second largest fresh water lake in the world. Its basin holds over 2,900 cubic miles of fresh water, which is replenished by over 200 rivers in its drainage basin. All of this water pouring into Lake Superior makes its way out again through a single outlet: The St. Mary's River. Originally, water from Lake Superior had to flow through the St. Mary's rapids, dropping a total of 21 feet before it reached the elevation of Lake Huron. Before the Soo Locks were built, cargo had to be unloaded from ships and portaged overland around the rapids, slowing transit and requiring expensive labor. The difficulty was so great that the British Northwest Company created the first lock on the north side of St Mary's River in 1797, large enough to allow 30-foot canoes loaded with furs and trade goods to pass through safely and without the long portage. U.S. forces destroyed this first lock during the War of 1812, but both U.S. and Canadian governments built additional locks during the centuries that followed to accommodate growing traffic on the Great Lakes. Quick Facts about the Soo Locks:

The first lock on the St. Mary's River was built on the north shore by the British North West Company in 1797. At the time, it controlled 80% of the Great Lakes fur trade, rivaling the Hudson's Bay Company for trade with the northwest territories. The 38-foot lock eased the passage of canoes between the territories and the North West Company headquarters in Montreal. The lock was destroyed by American forces in the War of 1812, but increasing traffic on the Great Lakes convinced the United States to build a lock of its own. State Lock was built in 1855 on the south (U.S.) side of St. Mary's River. This 350-foot lock was financed by a federal land grant of 750,000 acres. The opening of State Lock shortened the trip between Lake Superior and Lake Huron from seven weeks to seven minutes. The state of Michigan operated the lock until it became clear that a larger lock was needed to accommodate increasingly large ships traversing the Great Lakes. The operation of State Lock by the US became a sticking point in 1870, when the Canadian steamship Chicora was refused passage because of its military mission to quell the Red River Rebellion. Ultimately, the Chicora was allowed to pass through State Lock, but Canada resolved to build a lock under their own control at Sault-Ste-Marie, Ontario. Meanwhile, it was clear that State Lock was unable to accommodate increasing traffic and longer sizes of Great Lakes vessels, and in 1881 the new 515-foot Weitzel Lock was completed, operated by the US Army Core of Engineers. When it opened, the Weitzel Lock charged 3-4 cents per ton of cargo. This lock had an improved design, filling through openings in the floor, which reduced turbulence inside the lock. The All-Canadian Waterway finally opened in 1895, nearly a quarter century after the Chicora incident. When it opened, it was the largest lock in the world, at 900 feet long. Ship sizes and demand for passage through the Soo Locks continued to increase, and in 1896, State Lock was expanded to 800 feet long and 100 feet wide. Renamed Poe Lock, it was the first lock to use steel gates rather than wood gates. At construction, it could raise and lower 4 ships at a time. Only a few decades later, Great Lakes ships were already outstripping the size of Poe and Weitzel locks. The Col. James M. Schoonmaker, launched in 1911, was 613 feet long. The Davis Lock opened in 1914 to accommodate these larger ships: 1350-feet long and 80-feet wide. It was the first lock to use concrete rather than stone masonry for its walls and the first to have electric winding machines for gate operation. Construction of the Sabin Lock quickly followed, based on the same design. World War II dramatically increased the demand for Lake Superior's iron ore, so in 1943 the aging Weizel Lock was replaced by the MacArthur Lock, 800-feet long and 80-feet wide, to accommodate the deeper drafts of heavy-laden vessels. Renovations of the Poe Lock followed swiftly and its capacity increased to 1200 feet long and 110 feet wide by 1968. Poe Lock II was the first lock on the Great Lakes to accommodate a 1000-foot ship. In the 1980s, the Soo Lock on the Canadian side was irreparably damaged by a passing ship and permanently closed to commercial vehicles. However, in 1998, a new recreational lock, the Sault Ste Marie Canal, was constructed inside the old Canadian waterway, and remains open to pleasure crafts, including kayaks, sail boats, and private yachts. Today, the four commercial Soo Locks (MacArthur, Poe, Davis and Sabin) remain critical to industry and commerce in the Great Lakes region. The aging locks are due for an upgrade, and approval for an additional lock was granted by the US Congress in 1987, but two decades later, Soo Locks are still waiting for nearly $1 billion in funding to build the next generation of locks on the Great Lakes.

|

Welland Canal, Ontario, Canada

|

Read an overview of the Welland Canal at the Canadian Encyclopedia

Heading that way? Plan your visit at Niagara's Welland Canal website, and explore their wonderful map of the evolution of the canal. Some portions of the first three Welland Canals are still visible. Learn more about these historic sites at the Welland Canals Field Guide. For a virtual tour, you can even explore the historic canal using Google Earth. Can't wait to experience the Welland Canal by ship? Check out this HD time-lapse of a trip through the locks from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario.

Four cities reside alongside the Welland Canal. Explore them all via the scenic Welland Canal Corridor (part of the Greater Niagara Circle Route Trails System). |

<

>

Before the Welland Canal was built, the only water route connecting Lake Erie with Lake Ontario required a portage around the hazardous 326-foot drop of Niagara Falls. The Welland Canal Company was formed in 1824 and charged with constructing a direct route between the two lakes to remove this expensive and time-consuming process. The company constructed the first Welland Canal from Port Dalhousie on Lake Ontario to Thorold, Ontario. Here, boats could enter the Welland River take the Niagara River south of the falls. The first ship passed through the Welland Canal in 1829. The high demand allowed the Canal to be extended to Port Colborne on Lake Erie by 1833. This first Welland Canal was 27.5 miles long, with a total of 40 wooden locks, and teams of oxen to pull ships along the canal. The second Welland Canal was constructed in the 1840s, to reduce the number of locks and to replace the wooden construction with stone masonry, while also deepening and widening the locks to accommodate larger ships on the the Great Lakes. By 1870, it became clear that ships carrying grains, lumber, and ores from the Upper Lakes would prefer to travel through the Welland Canal, but it was too small for the larger steamboats that had gradually replaced the sailboats on the Great Lakes. A third Welland Canal update was approved to extend the locks to 270 feet long. A portion of the canal between Port Dalhousie and Allanburg was moved, to make the route more direct. The third Welland Canal was 26.75 miles long, and opened in 1881. The 4th and current Welland Canal was also built in response to increasing ship size. The project aimed to double the size of the locks on the previous canal. Construction began in 1913, but World War I interrupted it. The Welland Canal was completed in 1933, and all three of the former canals were decommissioned. In 1973, an additional modification was made to the canal, to bypass Welland, Ontario. The old canal route through the city has now become a recreational space for the Welland community. The Welland Canal is a 28-mile (44 km) navigational canal in Ontario, Canada

|

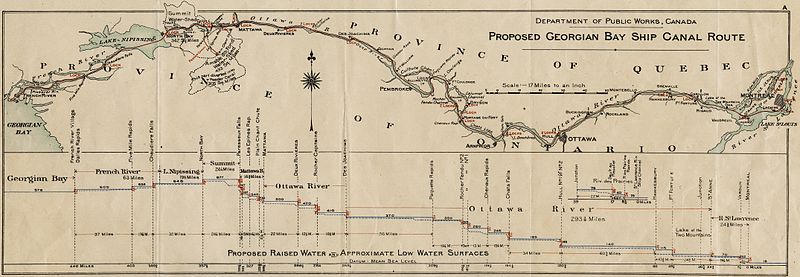

The Dream of a Georgian Bay Ship Canal

After the War of 1812, the British were painfully aware that the fledgling United States could interrupt traffic between the upper Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River colonies. Regional surveys were drawn up to determine a route between Lake Huron and Montreal that could cut out American influence or interference.

The original plan followed an old fur trading route along the French, Mattawa, and Ottawa Rivers, a nearly 40-mile trip and the "shortest route from the upper Great Lakes to the ocean harbour of Montreal."

The original plan followed an old fur trading route along the French, Mattawa, and Ottawa Rivers, a nearly 40-mile trip and the "shortest route from the upper Great Lakes to the ocean harbour of Montreal."

Surveys of the potential canal path in the early 1900s, however, proved that the canal would be a project on par with construction of the Panama Canal. The Georgian Bay Ship Canal would require 8 single and 3 double locks, with at total of 11 changes in water level. Furthermore, the canal would have to be blasted out of the Canadian shield rock. The probable construction cost was $100 million over 10 years.

The difficulties of the proposed canal were serious, and several other factors stood in the way. Railroad magnates pressured the government to focus on the construction of railroad tracks rather than canals. It was also clear that canals built in the United States, such as the Ohio & Erie Canal were not turning a profit. Further, competition between Toronto and Montreal heightened the political objections to connecting Montreal to the west.

So the Georgian Bay Ship Canal was lost to history, and the Great Lakes remained the primary conduit for industrial, commercial, and recreational traffic in the region.

Read more about "The Ontario that Almost Was" on the Northeastern Ontario Tourism website.

The difficulties of the proposed canal were serious, and several other factors stood in the way. Railroad magnates pressured the government to focus on the construction of railroad tracks rather than canals. It was also clear that canals built in the United States, such as the Ohio & Erie Canal were not turning a profit. Further, competition between Toronto and Montreal heightened the political objections to connecting Montreal to the west.

So the Georgian Bay Ship Canal was lost to history, and the Great Lakes remained the primary conduit for industrial, commercial, and recreational traffic in the region.

Read more about "The Ontario that Almost Was" on the Northeastern Ontario Tourism website.

Ohio & Erie Canal

|

|